Say what you want about The New York Times -- actually, don't say what you want -- the paper does have some great resources at its disposal. One of my favorite features is their city journal. That's where stringers and foreign correspondents file slice-of-life reports from exotic locales. This week the Times had a report from Chimayo, New Mexico, with a rather provocative headline: "A Pastor Begs to Differ With Flock on Miracles." Reporter Erik Eckholm's story is brief and you should read the whole thing, but here is how it begins:

"It's not the dirt that makes the miracles!" the Rev. Casimiro Roca said with exasperation.

True, discarded crutches line a wall inside the Santuario de Chimayo, a small adobe church in this village of northern New Mexico known as the Lourdes of America.

True, tens of thousands of pilgrims walk eight miles or more to the shrine on Good Friday, some bearing heavy crosses and others approaching on their knees. Scores of people visit every day the rest of the year, many hoping to cure diseases or disabilities with prayer, holy water and, most famously, the healing dirt, which visitors collect from a hole in the floor inside the church.

What a fantastic lede. Clearly we're dealing with Penitentes here! Considering the media interest in flashy religion stories, I'm surprised we don't get more coverage of them. Growing up in Colorado, I didn't realize they were such a small group but apparently Penitentes only exist in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. They are known for their self-flagellation and Holy Week processions. They used to be known for their mock crucifixions. When I lived in Colorado we studied them more in an historic context but while their numbers have dwindled from the 19th century, they still exist.

Sure enough, Eckholm explains that the original chapel was constructed by Penitentes. It fell into disrepair and Father Roca devoted his life to rebuilding the sanctuary -- including the hole -- and creating the shrine and gift shop. The gift shop sells plastic containers of "blessed dirt" and holy water, by the way. The story is rich with detail and begins to paint a picture of Father Roca:

Few leave without some of the reddish soil, scooped from the 18-inch-wide "posito," or well, that is continually replenished -- by a caretaker, Father Roca is quick to explain, despite rumors over the years that the pit was refilled by divine intervention.

He pointed to the small building nearby where trucked-in dirt is stored. "I even have to buy clean dirt!" he complained.

Eckholm interviews two of the visitors who take dirt and water home in hope of healing. Rosa Salazar, whose husband has cancer, reported that after rubbing dirt on her husband's chest and feet -- and praying -- his latest CAT scan looked better.

Father Roca believes in miracles, too, but, he said, "They are the work of the Good Lord."

"I always tell people that I have no faith in the dirt, I have faith in the Lord," he said. "But people can believe what they want."

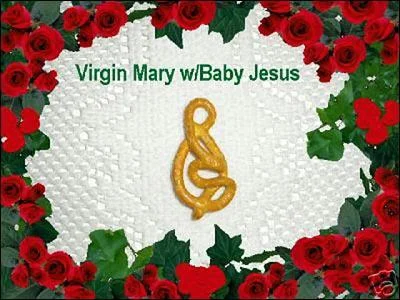

For all the stories we get about weeping statues and apparitions of the Blessed Mother or, um, Virgin Mary pretzels being sold on eBay, it's rare to see this side of the story reported on. The one question I felt was unanswered was what, specifically, Roca is doing to correct parishioners' and visitors' misguided views

As for the dirt, the best-known attraction of his busy little church, he said: "I don't like to think about it. People come here not for the crucifix but for the dirt, and some people even sell it."

Mrs. Salazar, the believer in its healing power, said she knew nothing of Father Roca's vexation. "I think the dirt gets blessed by the priests, doesn't it?" she asked.

The story is so brief that it's possible that too much would have been lost by delving into what the priest tells his flock and the visitors to his chapel. Still, it is a curious missing piece. But the article does provide other rich details that make the story come alive.