Rare is the week in which I don’t read two or three important stories in the mainstream press that leave me thinking: “Journalists are really going to need to understand the wild, complex and rapidly world of nondenominational evangelical-fundamentalist-charismatic-Pentecostal-Protestant-whatever churches.”

For starters, the vast majority of these church have absolutely zero connections to any group providing even minimal legal, financial, ethical or theological oversight. In many cases, the pulpit-star who started the congregation remains in complete control, with a hand-picked board as the only balance on his power. He may not have even attended an accredited seminary.

Think about that the next time you ponder the role of structures of “evangelical power” in stories about clergy sexual abuse or, oh, the odd riot at the U.S. Capitol.

This brings me (#NoSurprise) back to the world of researcher Ryan Burge (must-follow on Twitter) and a recent think piece he wrote for Christianity Today with this headline: “How ‘Christian’ Overtook the ‘Protestant’ Label.” Before we get to a Burge chart or two, here’s the overture:

Over the past several decades, American evangelicalism has moved away from the religious labels, symbols, and buildings that used to define church.

Many newer churches don’t contain stained glass, crosses, or traditional sanctuary setups. They tend to adopt contemporary names, leaving out denominational labels or other religious language. Along with those shifts, churchgoers have changed the way they speak about their faith; think of phrases like “It’s is not a religion; it’s a relationship.”

These trends have had a real impact on how younger people understand their religious identity. Evangelical Protestants have been debating for years over the definition and usefulness of the “evangelical” label. Now, it appears “Protestant” may be losing its place too.

Put the word “Baptist” on the sign in the lawn? No way. And, of course, there are zillions of different meanings to the word “Baptist” — in the world of independent churches. But that’s another (related) subject.

Burge is working, in this case, with numbers from a weekly Nationscape survey — a service created by the Democracy Fund in mid-2019. He notes that it “stands as the largest publicly available survey dataset in history, with nearly a half million people surveyed.”

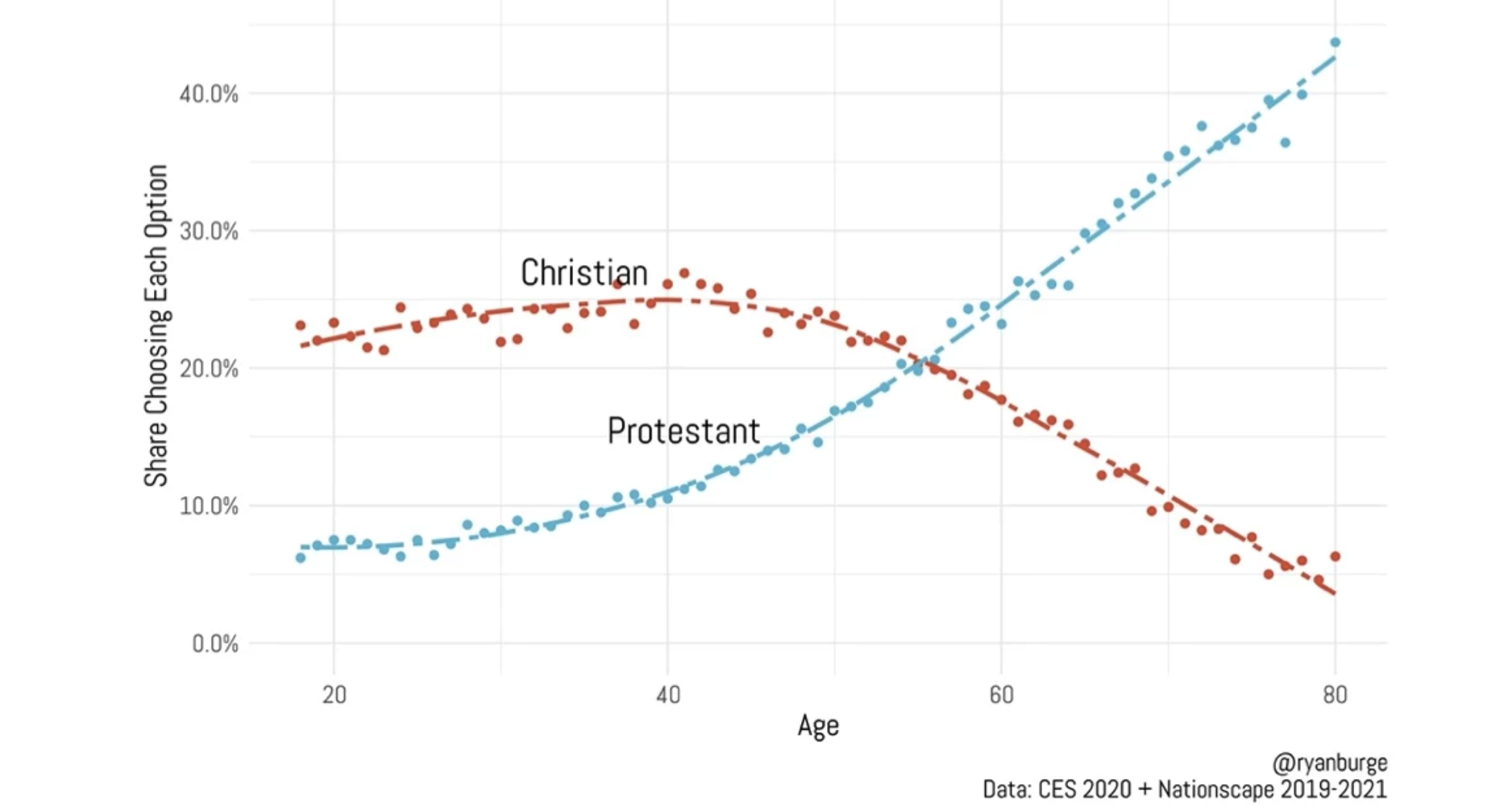

The researchers there give respondents the option to identify as Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox, or Christian, among other choices. Check out the generic “Christian” trend.

Burge notes:

The younger a person is, the more likely they are to prefer Christian over Protestant. Among 20-year-olds, 22 percent indicated that they were Christians, while 8 percent said that they were Protestants. At 40, 25 percent said Christian, and 11 percent chose Protestant. Around age 55, people are just as likely to say Protestant as Christian.

The oldest Americans clearly still identify as Protestant. About a third of 70-year-olds said that they are Protestants, with just 10 percent indicating that they are Christians. …

(The) shift corresponds to the recent history of Protestant Christianity. The rise of nondenominational Christianity and the decline of the mainline Protestantism began in the 1980s. People who are in their 50s or younger grew up in a world where Protestant terminology was falling out of favor.

This think piece is a door into an academic paper that Burge recently published at Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Journalists may want to file the link to that.

Now, I know what you are thinking: Burge is a political scientist, so there has to be a political angle.

Sure enough, there is.

There is some evidence that younger people who identify as Protestants are more likely to say that they are Democrats than those who say that they are Christians. For instance, 27 percent of white Protestants were Democrats, compared to 20 percent of white Christians. That gap also appears for Black and Hispanic respondents as well.

This may be because churches in the mainline tradition such as United Methodists and Episcopalians, which are more likely to still use Protestant as a label in sermons and literature, tend to be more politically moderate.

The implications of all this for journalists is stunning — at least for journalists who think that words matter in precise, accurate coverage. In this case, we are talking about words linked to facts about history doctrine, structure, authority, traditions and church law. That’s all.

Let’s end with this reflection from Burge, who readers should remember is also a progressive Baptist pastor:

From a social science standpoint, how people identify (or not) with a religious tradition is incredibly important. One of the key questions that human beings face is “Who am I? And who are people like me?” Religion is one of the ways in which Americans help sort themselves into social space. The Protestant identity helps Baptists, Methodists, and Episcopalians know that they share a great deal of commonality. When those labels begin to fade, there are fewer social signposts to aid people in finding like-minded people.

Read it all. This topic is only going to get more important as the digital niche age rolls on.